News | L.A. Expo Line Hasn't Reduced Congestion as Promised, a Study Finds

Stop the VideoNews

METRANS UTC

L.A. Expo Line Hasn't Reduced Congestion as Promised, a Study Finds

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

Repost of an L.A. Times Article by Dan Weikel and Alice Walton - Contact Reporters

USC researchers found that the 8.6-mile Expo Line did accomplish a worthy goal: boosting transit ridership in a dense, car-choked corridor. (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

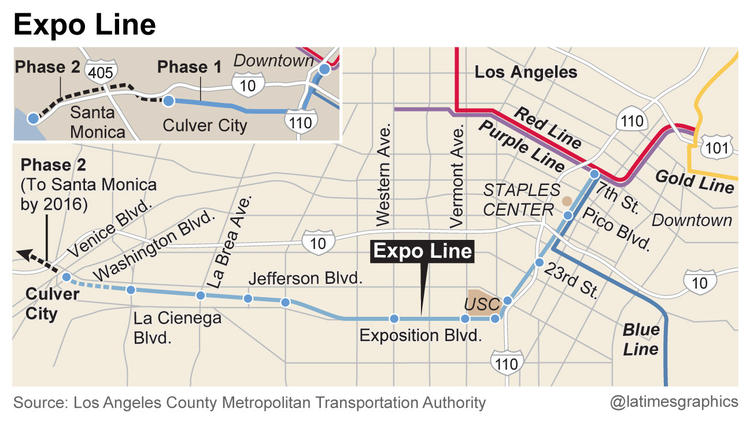

Contrary to predictions used to promote the first phase of the Expo light rail line between downtown and Los Angeles' Westside, a new study has found that the $930-million project has done little to relieve traffic congestion in the area. The analysis released Monday by USC researchers found that the 8.6-mile line did accomplish a worthy goal: boosting transit ridership in a dense, car-choked corridor. But the findings suggest that political and transportation leaders should rethink the way they market such transit investments to the public. Emphasizing reduced traffic congestion, researchers said, undersells more valid reasons for supporting public transit, such as providing transportation for low-wage earners, increasing links to job centers and providing more travel options. "Looking into the future, this study shows us how to be more realistic in what we should expect from transit," said Sandip Chakrabarti, a researcher at USC's Metrans Transportation Center, which conducted the study for the county's Metropolitan Transportation Authority. "There is a value in creating quality transit for those who use it by choice or by need. It improves productivity for a lot of people."

The study took morning and evening rush-hour readings from sensors placed along the Santa Monica Freeway and major arterials during two comparable three-month periods before and after the line opened in June 2012. Researchers found that transit boardings for both buses and light rail increased about 6% to 126,000 in the study area. But the presence of the rail line didn't have a significant or consistent impact on the average speeds of motorists on the freeway and major, nearby surface streets. The most noticeable increase — 2.02 miles per hour — was in the eastbound freeway lanes during the morning rush hour. During the evening peak, average speeds in the eastbound lanes decreased by 1.27 mph. Other peak-hour speeds on the freeway and major arterials, such as Venice, Martin Luther King and Washington boulevards, scarcely changed or showed mixed results. The numbers of people shifting from one travel mode to another "are unlikely to be large enough to influence transportation system performance across the highly congested corridor served by the Expo Line," the study states.

The Expo corridor crosses one of the more heavily populated and congested areas of Los Angeles. There are about 26,000 people and 11,000 jobs per square mile. During rush hours, the Santa Monica Freeway and major city streets are routinely clogged. At the time of the study, motorists made about 500,000 trips per weekday through that section of the city and the Expo Line, operated by the transportation authority, reported 20,000 boardings. Andres Cantero of Long Beach, a law student at USC, takes the train to school five days a week. "For me, it's an opportunity to study and not waste time in traffic," he said. "Very rarely do I drive." The researchers cautioned that it might be too early to draw firm conclusions about the effects the Expo Line may have. Ridership is changing rapidly, they noted, and hasn't stabilized. Metro officials said the study offers important information but defended the Expo Line's performance, saying it currently has more than 30,000 daily boardings, exceeding ridership projections. Recent surveys indicate that people living within half a mile of the Expo Line have been reducing their reliance on motor vehicles.

News Archive

- December (1)

- November (6)

- October (4)

- September (2)

- August (3)

- July (4)

- June (3)

- May (7)

- April (8)

- March (11)

- February (8)

- January (7)

- December (7)

- November (8)

- October (11)

- September (11)

- August (4)

- July (10)

- June (9)

- May (2)

- April (12)

- March (8)

- February (7)

- January (11)

- December (11)

- November (5)

- October (16)

- September (7)

- August (5)

- July (13)

- June (5)

- May (5)

- April (7)

- March (5)

- February (3)

- January (4)

- December (4)

- November (5)

- October (5)

- September (4)

- August (4)

- July (6)

- June (8)

- May (4)

- April (6)

- March (6)

- February (7)

- January (7)

- December (8)

- November (8)

- October (8)

- September (15)

- August (5)

- July (6)

- June (7)

- May (5)

- April (8)

- March (7)

- February (10)

- January (12)